The Confederate Treasury made a consequential decision upon its inception: to have the Register and Treasurer hand-sign each and every printed Treasury note. With the idea that this would deter counterfeiting and that the war would be short, this decision seemed reasonable. The first series of Treasury notes numbered a few thousand, all of large denominations – $1000, $500, $100, and $50 – and they were signed by Treasurer Edward Elmore and Register Alexander Clitherall. The U.S. Treasury decided to use machine printed signatures on their “green back” Treasury notes, so U.S. Treasurer Francis Spinner and Register Lucius Chittenden did no hand-signing. If the war were short, this decision to require hand signatures would have had little consequence. However, the war dragged on for four years, and in the end, the Confederacy printed over $1.5 billion in Treasury notes, many in small denominations of $1 to $20. This meant that the Confederate Treasurer and Register would have needed to sign nearly 80 million notes, totaling 160 million hand-signatures. This was clearly impossible for these two individuals, given all else that the Treasury needed to accomplish. So they established a Treasury Note Division to not only contract printing of notes but with clerks to sign, cut, number, date, and trim the notes. At first, the Treasury Department hired 19 men as civil servants, working in pairs, to sign notes. As the war progressed, however, many more men were hired. Indeed, with men needed in the army, the Treasury began to do what it never had before: hire women in government positions. Over the course of the war, the Confederacy hired 367 clerks to sign their Treasury notes, and many more to handle other Treasury jobs. By April 1864, all signing clerks were women. On final tally, about two-thirds of the 367 signing clerks were women, and of those women, about two-thirds were single. Many were young, in their teens or twenties. Most were of high social standing, privileged, educated, and with excellent penmanship. Financial need was important, but the clerkships typically went to a higher social class, often with nepotism.

What were the consequences of this decision by the Confederate Treasury to have two hand-signatures on each note? One consequence was an enormous administrative cost to the Treasury. We estimate that the Confederate Treasury spent about $75 million (adjusted to 2022 dollars) in salaries to the signers. Beyond this cost were salaries for other clerks that hand-numbered or hand-dated notes, and for the signing supplies including pens, ink, and clamps. Furthermore, having signing clerks required infrastructure, such as buildings, desks and other furniture, and salaries of chief clerks who managed the signing clerks. These costs significantly raised the cost of affixing two hand-signatures on every Treasury note. The Confederate Treasury recognized this cost in dollars and effort, and recommended to the Confederate Congress to allow it to machine print signatures. But Congress did not allow this. Why? One likely factor is that Congress considered the hiring of signing clerks as a form of welfare, of course for the upper class who found themselves in need. A second consequence of this decision to hand sign notes was not intended but was of enormous and long-lasting social consequences. The war-time Confederate government employment of Treasury ladies affected their roles and relationships at home, as it gave them experiences, opportunities, and responsibilities that women never had before. It also gave these women post-war work opportunities and choices that women before them never had. Would those Treasury ladies who were single take the more traditional role of young women and get married and raise a family? Or would they choose to continue working, for the government or in other occupations and careers? If they chose to pursue a career, would they also be able to marry and have children? Perhaps they would choose to sacrifice that path, or even consider it a liberation. Susan Barber showed that while white wage-earning women comprised only 1.6% of the free labor in the Richmond workforce in 1860, by 1870 this figure had risen to 9.9%. As for the Treasury ladies, after the war, many of them had significant public lives and exceptional accomplishments. Many continued careers with the government, either state or national. Others had careers as writers, educators, school administrators, scientists, inventors, and community leaders. Many never married. These women were highly representative, even leaders, in the social transformation that occurred in the post-war South. For example, Susan Archer Talley was a writer and artist, friend and historian of Poe, and Civil War spy and seductress. Etta Kelly was an entomologist, U.S. agricultural commissioner, founder of Charleston Female Academy, educator, and mentor. Amy Yates Snowden co-founded the Home for the Mothers, Widows, and Daughters of Confederate Soldiers, which provided support for poor female dependents of Confederate soldiers, and a school was established for their children, the Confederate Home and College. Mary Spear Nicholas Tiernan was an acclaimed writer of novels, poetry, and short stories including Two Negatives about the lives and loves of the Treasury ladies and co-founder of Woman’s Literary Club of Baltimore. Lizzie Elliott was a poet, teacher, and dean at Sam Houston State University. Henrietta Porcher Heriot worked in the U.S. Treasury Post Office and was a powerful role model for her daughters. Sanders Jamison, Chief of the Treasury-Note Bureau, in his report to Treasury Secretary George Trenholm on October 31, 1864, reflected on their experiment of employing women to do the work previously done by men. Jamison wrote, “In closing this report I must be allowed to speak in the highest terms of the ladies and gentlemen who have been associated with me in getting out the work of the office. The experiment of employing ladies in the public offices, first instituted by Mr. Memminger, has not only proved a perfect success, but has been the means of relieving the necessities of many who have been driven from their homes and have lost all by the barbarous cruelty of our inhuman foe.” Indeed!

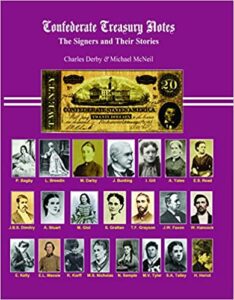

The Confederate Treasury Notes: The Signers and Their Stories by Charles Derby and Michael McNeil highlights include…

- Introduction with a history of the Confederate Treasury Note Bureau and the professional activities of the Treasury note signers within it

- Original research on the 371 signers of Confederate Treasury notes, some of whom also signed bond coupons. The book includes photographs of the signers and their lives

- Section coupling an image of the signer’s signature and name for quick identification of the signer on any Confederate note

- Two-page list of signers for the Register and Treasury, updated from Thian’s Register

- Appendix with writings by and about the Treasury note signers

- Extensive bibliography

- Available as a 360 page soft cover book with perfect binding, 8½ inch by 11 inch

To order the book, send $49.95 plus postage ($5 domestic, $10 international) to Charles Derby, 204 Sycamore Ridge Drive, Decatur, GA 30030. Option to use Venmo or Zelle. For more information, contact charlesderbyga@yahoo.com.